MODULE 5

MODULE 5

In this module, you'll explore three key steps in the process of improving your understanding of a system:

A good systems map is an accurate representation of how a portion of the world works. But you inevitably have limited information and perspective. In order to develop an accurate mental model and systems map, you need the input of stakeholders—people who are affected by or who can affect a system's operation.

A mental model is a manifestation of a person's conscious or unconscious understanding of how some part of the world works. It is a representation of:

In effect, a mental model is an unarticulated systems map. Mental models are essential to making sense of our everyday activities and interacting with other people or the physical world.

Watch the video to learn more about mental models, how to translate them into systems maps, and how mental models can change.

We need mental models. They are essential for processing the constant flow of information that our brain receives every moment through sensory input. But we’ve just seen that mental models can have serious limitations. Here's another example of a mental model that was not subjected to adequate double-loop learning.

An intervention premised on a flawed mental model is unlikely to achieve its goals and is prone to unintended adverse consequences. This is exemplified by the invasion and occupation of Iraq in 2003, carried out by a Coalition of forces led by the United States.

Provoked by al-Qaida's terrorist attacks of September 11, the Coalition's military actions did not achieve their desired outcome and instead resulted in catastrophic unintended consequences.

| Desired Outcome | Actual Outcome |

|---|---|

| Combat terrorism | Enabled the recruitment of terrorists and the rise of the Islamic State |

| Eliminate Iraq's weapons of mass destruction | No weapons of mass destruction were discovered in Iraq, and Iran was indirectly brought closer to having nuclear weapons |

| Facilitate Iraq's transition to a stable democratic, representative self-government | After two decades, Iraq is far from that goal |

Let's examine the assumptions that led to these outcomes and how the Coalition might have revised those assumptions by learning from feedback.

The Coalition's leaders went into Iraq with a well-formed mental model about what would happen. As journalist George Packer described it:

"Plan A was that the Iraqi government would be quickly decapitated, security would be turned over to remnants of the Iraqi police and army, international troops would soon arrive, and most American forces would leave within a few months. There was no Plan B."1

The Coalition functioned effectively during the invasion of Iraq and the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. Yet things soon went terribly wrong—in large part due to the Coalition's neglect of security and its failure to learn from feedback and adjust its mental model of the occupation.

Early in the occupation, Coalition forces failed to act during weeks of civil unrest and unchecked looting. This inaction cost lives and destroyed essential infrastructure—including electrical and water systems. It also resulted in trashed government and university buildings and museums.

The Coalition banned tens of thousands of members of the governing Ba'ath Party from government service and disbanded the 400,000-man Iraqi army, leaving many powerful and disaffected Sunni unemployed and angry. This situation fueled the growth of a huge insurgency movement.

American diplomat Peter Galbraith, who supported the invasion, subsequently wrote:

"I never imagined that the Bush administration would manage the post-invasion period as incompetently as it did. I never thought that we would enter Baghdad without a plan to secure any of the city's public institutions. I never imagined that the administration would assume it had no responsibility for law and order."2

Watch the video to learn how a flawed mental model led to a lack of security that the country still struggles with many years later.

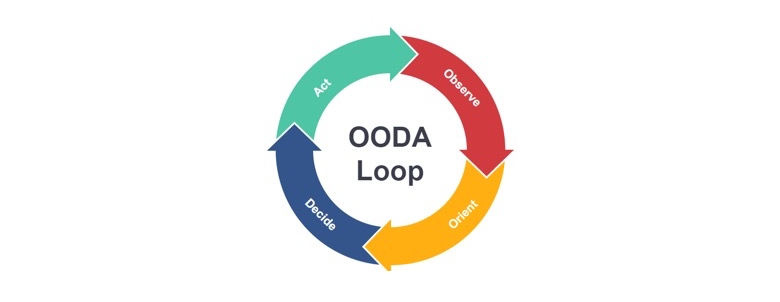

Decades before the invasion of Iraq, U.S. Air Force Colonel John Boyd applied double-loop learning—getting feedback and modifying the decision rules and mental model—to military strategy. He called it the OODA loop: a cycle of observe—orient—decide—act. Boyd noted that changing a strategy based on new information was essential to military victory.

In the case of Iraq, the Coalition failed to engage in the observe and orient steps of the OODA model. As Larry Diamond wrote:

"The collapse of public order in the aftermath of the war had devastating long-term consequences…. It opened Iraq's vast borders to the infiltration of Al Qaeda and other Islamist terrorists, suicide bombers, Iranian intelligence agents, and other malevolent foreign forces. It left Iraq's vast stores of arms—an estimated one million tons of weapons and ammunition—substantially unprotected, and thus ripe for plucking by criminals and insurgents. It gave an opportunity for every ambitious opponent of a democratic Iraq—domestic and foreign—to rush into the void. Moreover, the chronic disorder made it difficult to carry out the functions of economic, civic, and political reconstruction."3

There were many opportunities for the Coalition to learn along the way. What prevented the Coalition from understanding what was happening in Iraq and modifying its mental model to avert these dire consequences?

How and when do mental models change? Typically, when they can no longer account for the facts they are designed to explain or justify. But there are many barriers to revising mental models. To begin with, a mental model is often unconscious: it's just the way you see the world. Revising a mental model typically requires bringing it to consciousness and articulating it.

But we are well-defended against revising mental models. Confirmation biases, personal and institutional commitments, fear of change, loss of control, and just plain ego make us resist evidence that doesn't conform to our existing beliefs.

These barriers are relevant not just to local decisions, such as the hiring of women faculty or the occupation of Iraq, but to the mental models that serve as fundamental scientific paradigms.

For much of human history, astronomy posited that the sun revolved around the earth. But in the 17th century, the Italian scientist Galileo, building on the work of Nicolaus Copernicus, argued that astronomical observations proved that the earth actually revolved around the sun. In addition to other barriers to revising a venerated mental model, Galileo's view violated Roman Catholic doctrine and led to his being punished for heresy.

Many barriers to revising mental models, including President Bush's zeal to oust Saddam Hussein, were at work in Iraq. They were compounded by the military's inevitable hierarchy, which discouraged the line personnel who saw what was happening on the ground from contradicting their superiors. Writing in 1981, the British military historian Sir Michael Howard observed:

"It is not surprising that there has often been a high proportion of failures among senior commanders at the beginning of any war. These unfortunate men may either take too long to adjust themselves to reality, through a lack of hard preliminary thinking about what war would really be like, or they may have had their minds so far shaped by a lifetime of pure administration that they have ceased to be soldiers."4

Perhaps for these reasons, as well as their belief in the righteousness of their cause, neither senior White House personnel nor the Secretary of Defense were open to feedback during the occupation of Iraq.

It is no exaggeration to say that we depend on mental models to understand and navigate the world we encounter every moment of the day—from brushing our teeth to commuting to work and doing our work, to cooking dinner at night. Writing specifically about businesses, Stanford Professor Jeffrey Pfeffer notes:

"Every organizational intervention or management practice—be it some form of incentive compensation, performance management system, or set of measurement practices—necessarily relies on some implicit or explicit model of human behavior and beliefs about the determinants of individual and organizational performance. It is therefore just logical that (a) success or failure is determined, in part, by these mental models or ways of viewing people and organizations, and (b) in order to change practices and interventions, mindsets or mental models must inevitably be an important focus of attention."5

Pfeffer's examples of revised mental models include Toyota's radical restructuring of the automobile manufacturing based on teamwork, continuous improvement, and just-in-time inventory.

Here are some mental models that have been particularly resistant to change:

We need mental models to make sense of the world, and yet our mental models are often flawed. As systems thinkers, we are called upon to bring our mental models to the surface, examine them, and improve them. To do this: